“Misremembered

Days”

(by Antony Mann – 2008)

*

Begin | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07

|

“Part I –

Beginnings” I wasn’t there at the beginning, which by all accounts

took place on December 31st 1997 at Jude The Obscure, in those days a

Jericho pub run by Noel Reilly. Jude

The Obscure remains a Jericho pub, but the landlord is no longer Noel

who, some say, made the establishment too successful for his own good, and

consequently had his contract terminated by the brewery. Noel was an Irishman

who took delight in the arts, and during his tenure at The Jude, short films, plays, book launches

and musical events were the norm. The Catweazle Folk Club

made its home there for a short while before being kicked out because all the

heads wouldn’t buy beer, man. I still remember

sitting cross-legged on the floor watching cute barefoot canal boat chicks

with smudged cheeks and marijuana eyes telling stories about the moon from

the moon’s point of view.

Early days,

outside the pub. A blurred Noel Reilly front row second from left. It was this rarefied hothouse atmosphere, this Little

Bohemia, which saw the idea of a cricket team emerge on New Year’s Eve of

1997. Credit for the founding of the club must go to Eddie Lester, an old

friend of Noel from the latter’s days as landlord of The Beehive in Swindon. Noel at once backed the plan with hard

cash for the purchase of bats and pads and gloves, some of which still remain at the bottom of the original kit bag, an

archaeologist’s dream. And, unlike so many wishful ideas conceived of on a

boozy night when everything seems possible and the practicalities are yet to

be faced in the cold light of day, the team actually came

into being. From the start, Eddie was the driving force, optimistic and

determined, in harmony with the whimsical patronage of Noel. Where cricket

had not dwelt before, cricket now would. |

Begin | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07

|

“Part II –

1998” Records for the first season of Jude The Obscure CC are understandably sketchy and incomplete,

for who could have known then that now, records would be of any use at all?

Few were kept, and of those that were, many have now been sadly lost. Of those

that were kept and not lost, many are inaccurate, and of those that were

kept, not lost, and accurate, most make depressing reading. The word went out, and players were gathered from here

and there, i.e. the pub, or places people went to after the pub had closed.

It is known that the first captain of Jude

the Obscure CC was Eddie Lester, or possibly Fred Townsend. Of players

available for selection in 2008, only Antony Mann (4 games in 1998) and Matt

Bullock (5 games) remained from that first season. A document entitled Jude The Obscure Cricket Team 1999

Pre-Season Newsletter does exist, and refers

back to 1998 on several occasions. It seems likely that The Jude won no more than two of the eight games in their first

year: a 7-wicket victory against South

Oxford Social Club (a team which no longer exists) at Cutteslowe Lower

Ground (a venue which no longer exists) in which Simon Brandon scored 86 (a

then-record which no longer stands); and a comfortable win against The Beehive in Swindon (L. Davie 67, F. Townsend 5-24, S. Pollard

2-17). There were losses against Oxford

Nondescripts, The Team With No Name, The

Beehive at home, and Research

Machines, whoever they were. It was Simon Brandon who in 1998 topped the batting

averages with 42.00 from 5 matches. He also took 6 wickets at 17.67 and

justifiably won Player of the Year. Simon was a young sporty guy, always

welcome because he brought along his girlfriend. She was a hot chick who wore

mirror sunglasses, whom God had created specifically for sitting in the sun

watching cricket, and other things best left to your imagination. Where are

they now, those two, Simon and the sunglasses chick? Where? Eddie Lester’s highest score in 1998 was 33 not out. He

was a correct-looking batsman but had a weakness for playing across the line

which would plague him in later years. He bowled looping spin with a

slow-motion slingshot action, and looked a bit liked

Lasith Malinga running through jelly. In those

days, in fact always really, up until the year he left, Eddie was the heart

and soul of the team, a tall gangly specimen with a shock of tousled blonde

hair who exuded an almost otherwordly enthusiasm

and optimism. Sometimes that faith in human nature and the weather was borne

out, sometimes it wasn’t. But the sun was always

shining for Ed.

The Jude’s

first skipper, Eddie Lester. Howard Jones was The

Jude’s first real quick bowler, and he took a wicket with his first

delivery for the team. He also batted with an aggressive, natural style which

sometimes saw him go early, but more often took him into the 50s and beyond,

though he never managed to score a century. His temperament meant that his

mind wasn’t always on the game, but Howard was a

founding member who had a massive impact on the side. He’s

someone who is missed to this day. In 1998, James Blann scored

46 runs at 6.57 and took 4 catches, but is best remembered

for the time meningeal fluid leaked out of his nose as he dived for a catch.

Meningeal fluid is the stuff which is in your head where your brain is. It’s white, like runny snot. I can’t

remember now why it leaked out of his nose, but I do remember we all stood

round watching and went, Oh, really? Is

that meningeal fluid? Well how

about that, huh? Naturally James shrugged it off

and kept on playing, like we all would have. Antony Mann joined the team late in the season after

Eddie turned up at a party in Walton Well Road, looking for players for the

next day’s game. Because he was an Aussie, everybody thought he would be a

shit hot ringer, and was just being modest when he said he was crap, but the

truth was he hadn’t played cricket since he was 12.

He was determined not to be crap forever, though, and went through the entire

season not out, earning the nickname ‘Blocker’. Which is me. Matt Bullock

joined around the same time Ant Mann did, and was destined to stay the

distance as well. The wry and phlegmatic Brummie became the team’s default

wicket keeper, then over the years the Chairman, chief statistician

and primary Voice of Reason, which is often useful among The Mad.

Noel Reilly

(centre) is escorted by his nieces to another den of inequity. Other Jude

players that year included the affable Martin Hurley, a left-hander who

batted like he was in the middle of a game of hurling, which was kind of a

weird coincidence when you looked at his surname, but not so weird when you

remembered he was Irish; and Chris Legg, a rough diamond who managed The Jude itself. He knew how to hit a

ball and in those days was a batting mainstay. He also bowled fast, quite

often at your head. Then there were John Moore and Richard Blann, who with James Blann and

Simon Brandon made up the team’s quartet of young dudes. Sam Pollard, with

his thin, hunched frame and wiry dark hair, who ran the second-hand bookshop

on Walton Road when it first opened. Noel Reilly himself, habitually bent

over even when not at the crease, played two games. Other people. A guy

called Kevin. As for how it was

in 1998, I don’t remember much, apart from how it

felt. It seemed as though there was now a fabric to the summer, newly woven,

a fabric which hadn’t been there before, as yet stretchy and flimsy and

liable to blow about in the wind unless held down by a big rock, but a fabric

nonetheless. But the question remained. Would that – could that – fabric be

made into an item of clothing, a shirt, perhaps? Would that shirt be a

cricket shirt, by any chance? Was that metaphor really

necessary? |

Begin | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07

|

“Part III –

1999” The Jude The

Obscure Cricket Team 1999 Pre-Season Newsletter is necessarily full of

bad jokes, but also talks in some detail about a Committee Meeting held in

March of 1999 in which it was mooted that elections for committee positions

should conceivably be held, although, what’s the rush? The possibility of

running a Saturday League team along with the Sunday side, in the manner of a

proper cricket club, was also raised. This is an idea often mooted by Sunday

pub teams, usually about once every two or three years, but it is rarely

acted upon. The transition from casual to ‘proper’ team is fraught with

difficulties. League teams need to provide a ground, train up their own

umpires, have insurance, answer to pernickety and unreasonable local

committees, and worst of all, turn up for games. Sunday teams just need to be

able to drink a lot. In addition, even though every Sunday player harbours a

secret desire to test themselves against Saturday opposition, every Sunday

player also knows that league teams are overflowing with ridiculous prima

donnas who take themselves and the game much too seriously. Sometimes these

Saturday guys turn out for their Sunday teams. You can tell who they are by

the way they screech in pathetic indignation whenever a decision goes against

them. Even in those early times, members of The Jude’s ‘ghost’ committee were

fully aware of the need to maintain an authentic Sunday ethos and to preserve

the individual’s right, while playing sport, not to be a sportsman. It is

this philosophy of Sundayism which has underpinned

the development of Jude The Obscure CC

in all its incarnations, and helped to forge the spirit of the side, creating

a small bastion of competitive fun in a world of barbarism and malaria. The Jude of

1999 was comprised entirely of Sundayists, and

there was little to distinguish them from the intake of 1998, although of

course some faces were new, and other players had got so pissed off with the

message Eddie left on their phones after they failed to turn up for the

mid-week game against St Clare’s,

they left in a huff. Of Simon Brandon, there was no sign. Nor did his

girlfriend appear to be anywhere about, nor her sunglasses. Where had they

gone? This is a rhetorical question and doesn’t

require an answer. The small, tight group of young dudes – James and Richard Blann, James Moore and John

Moore – played only six games between them in the whole season and were never

heard from again (see above, phone call, pissed off etc). But much of the core of the 1998 side remained, notably

Howard Jones, Chris Legg, Eddie Lester, Antony Mann, Matt Bullock, Martin Hurley and Fred Townsend. Fred was a big Londoner with an

easy manner who had soon married local girl Tash and headed off to Swindon.

In the meantime, he played a couple of seasons for The Jude, his career cut short by an irreparable rift with Noel

Reilly which saw him banned from the pub and thus the team. Fred thought of

himself as something of a batsman, but never scored any runs, and in the

field was most often to be found at mid-off with his thumbs hoiking his cricket trousers up past his waist. There

were new recruits as well. Alongside Clare Norris and Mike Thorburn, 1999

also saw the debut of James Hoskins, and father-and-son combo Tony and Ben

Mander.

Ben (left) and

Tony Mander (suit) join the ranks of Jude The Obscure. The Jude played thirteen games in

1999 under the continuing captaincy of Eddie Lester, winning four, drawing

two and losing seven. The good teams made up of experienced players, such as Isis and The Team With No Name, usually beat The Jude easily, whereas against the poorer sides such as

Weymouth’s The Quayside Occasionals, comprising local clowns and pissheads

dragged at short notice from the pub or gutter, The Jude had more of a chance. The Jude’s sole proper victory in 1999 came against The Marlborough at Cuttleslowe

Upper Ground, the first of many encounters between the two sides in the

seasons to follow. One thing Sunday teams need is someone to play against,

and the best kind of opposition is that which comes back year after year,

allowing rivalries and even friendships to develop. Sunday teams in the same

area often end up trading players as one team dissolves and another springs up to fill the void. The average lifespan

of a Sunday cricket team is 8.2 years, although of course some go on for much

longer than that. Any Sunday team which can’t make

it to 5 years just isn’t trying, though conversely, any Sunday side which

makes it past 25, or which boasts celebrities amongst its ranks, is showing

off. Despite a fine 102 out of 166-8 from Mike Reeves, The Marlborough went down by 4 wickets

thanks to a colourful 68 from Lee Davie, one of several important Davie

innings for The Jude over the

years. This was not the last The Jude

would see of Mikes Reeves, a left-handed batsman and bowler with an unusually

large head, though not elephantine or freak-show size by any stretch. As for

Davie, he was an aggressive batsman, fine fielder, handy left-arm bowler and sharp wicketkeeper. More importantly, he was

also a renowned local quiz night specialist. Some years later, sadly, he was

to suffer a horrific plastering injury that would see a Stanley knife all but

sever his head from his body at the neck. Or maybe that was just a bad cut on

the finger.

Lee Davie

sporting his new winter wardrobe. Victory against Marcham,

reaching their total of 85 with 5 wickets to spare despite playing with only

nine men, was achieved primarily through Stanton

St John Willows ringer Simon Dickens in one of his only two ever

appearances for The Jude. Called up

at three minute’s notice to fill in for the bastards who promised they’d play

but didn’t show, Dickens took 6-23 opening the bowling on an uneven pitch and

then scored 13, hitting the winning runs back over the bowler’s head while

stand-in skipper Ant Mann remained as usual nought not out watching from the

other end. At that time Simon Dickens was manager of the Threshers on Walton Street, and in

1996 had sold me the booze for my wedding. Funny how, years later, well,

three years, we would together play such an important role in a victory for The Jude, well, funny how he did

anyway. Like most players, I usually overestimate the importance of my

contribution to any game. For instance, if I make a stop or two in the covers,

take 1-23 and make 2 with the bat coming in at number eight, I still fancy I

might be up for Man of the Match for my all-round brilliance and am surprised

when some half-century scoring clod gets the award instead. It’s also a well-known fact that from

a bowler’s point of view cricket is a batsman’s game, though no amount of

whingeing about it will make a batsman give a damn. Bowlers win matches, are

generally good-looking and intelligent, kind to animals, and the sort of

people you’d want to have with you in the trenches.

Batsmen on the other hand are usually overrated, are a bit thick and tend to

be distracted easily by bright shiny objects. Being a bowler myself, I know

what I’m talking about. The best batsman in the world can walk out to the crease

and get bowled first ball, but no-one will blame him, because he ‘got a good

one’. Hmm, bad luck, that was unplayable. Nothing you can do when you get a good

one like that. Sympathy rains down on the unfortunate batsman from all

sides, just because he got a decent delivery. Meanwhile, the bowler can send

down a torrent of fantastic stuff, the best he has ever bowled, but

continually miss the edge and the stumps by millimetres, or if he does catch

an edge, have it dropped in the slips (usually made up of batsmen). But

nobody remembers that. They look in the wickets column and all they see is

the big fat zero. Oddly, though, everybody would rather bat than bowl,

especially in Sunday cricket. Batting’s just more fun, and all you need is a

quick 25 to get Man of the Match, whereas a bowler needs at least five

wickets against top-class opposition, and even then

there’s no guarantee. The Jude might well have beaten The Team With No

Name at Horspath that season after scoring only 71 all out (Lee Davie

34), if not for a torrential downpour which ended the contest with the

visitors in tatters on 8-4. Howard Jones’ spell of bowling that day was the

most venomous that any Sundayist had witnessed.

Howard was an often sensitive soul, and Fred

Townsend at mid-on, his pants as usual hitched up to his chest, spent the

time between deliveries goading him and telling him that the opposition had

been insulting him. Consequently, Howard took 3-3 against a strong top order,

in doing so showing the kind of form which saw him deservedly win 1999’s

Player of the Year trophy. His overall bowling average of 18 wickets at 13.94

(best of 5-9) was second only to Simon Dicken’s 9 wickets at 9.44. Jones also

topped the batting averages with 242 runs at 26.89 and a top score of 53. 1999 saw The

Jude’s first Tour, to Weymouth, organized through Eddie Lester’s

connections with Nigel Sawyer, another old friend of Noel Reilly from the Beehive’s honeyed days.

Nigel has since come north to live in Oxford, so track him down and buy him a

lemonade. The tour was the usual mix of fruitlessly chatting up chicks,

successfully passing out on various floors, and playing cricket at Bridehead in Little Bredy in

the private grounds of local landowner Sir Richard Williams. Indeed, “stepping onto the field

of play, the Jude team might have imagined that Mother Nature herself had

reserved this moment for them to wonder at and savour, that the splendours of

an enchanted English summer were encapsulated in this one day. The whole vale

seemed to ring with the echoes of past summers, just as their being there

today would echo into the future; just as their voices echoed now from the

surrounding hillsides.” In other words, a

non-paying crowd of buzzards, sheep and cows saw The Jude win handily

against the Occasionals. Apart from all that bucolic farmer-boy stuff, the

highlight of the tour was the entire team spending three hours on a

pebble-strewn beach throwing rocks of various sizes at a plastic football

until, with the sun setting, the ball had at last been forced down the sand

and into the water. Jeez, it makes you wonder – because I really do remember

that afternoon being a lot of fun.

The Jude on tour

in 1999. Eddie Lester is middle row second from right holding a bat. Chris

Legg front middle. Chris Legg’s top score for Jude The Obscure CC

in 1999 was 49. He was second in the averages with 162 runs at 20.25, and took 13 wickets at 19.31. Eddie Lester was

third in the batting averages with 152 runs at 19.00 and a top score of 32

not out. His best bowling figures were 3-11. This season, in only six of his

eleven innings did Ant Mann finish not out, with a high score of 31. Matt

Bullock played in all 13 games in 1999, scoring 67 runs at 7.44. In Martin

Hurley’s last full season for The Jude his top score was 20. Fred

Townsend managed 5 games, 12 runs and 1 wicket before he was banned from the

pub by Noel for that ‘incident’. I can’t even

remember now what it was all about. In fact, to be honest, nobody ever told

me. Bastards. Mike Thorburn registered a series of drunken

ducks before getting his act together and scoring 51 pissed runs at a

slaughtered 6.38. Mike liked a drink, especially when he was conscious, and

was also a useful half-tanked length bowler with a knack for taking wickets

while boozed up – 5 in 1999 at 14.80. Clare Norris stood out from the rest of

team because she was an Oxford Blue who could actually play

cricket. She was also a woman, and down the years the only woman who could

play cricket to play cricket for Jude or Mad. Her only problem

was getting the ball off the square, which meant that despite her correct

play, she wasn’t good for that many runs. In that

sense, and with the long hair and all, she was a bit like Jake Hotson in a

skirt. Not that I’ve ever seen Jake Hotson in a skirt,

and to be frank, it’s not high on my list of things to look at. Ben Mander played his cricket in a rough and

ready way, almost like a rugby player. He had the rugged good looks which

many cricketers aspire to when they first start playing, and the ability to

drink 26 beers on the night before any given game, then turn up having had no

sleep still drunk and yet even then a decent bloke, but he tended to hold his

bat rigidly at the crease, and when he did hit it, it was with no backswing

at all. His bowling was head-down spin, Windmill Variety No. 3,

unpredictable, and thus often potent. His father Tony, a noted gynaecologist,

was a steady batsman who always played his best when asked to fill in for the

opposition. Then, playing against his own team, he was transformed

from a calm blocker into a violent stroke-maker and sledger. After hanging about on the Cuttleslowe

boundary watching The Jude play for most of an afternoon, James

Hoskins was finally invited onto the field and as it transpired, into the

team. In his 10 games in 1999 he scored 15 runs at 2.14 and took 3 wickets at

26.00. The friendly James – or J-Mo – soon became one of The Jude’s

core players. Competitive, naturally open and

friendly, almost at times as optimistic as Eddie Lester, James was the player

most likely to approach the complete stranger sitting on the pier and ask him

what type of fish he was trying to catch. As with many Jude players,

he started out knowing not much about cricket, but over the years developed

the skills which made him a dangerous bowler and a key part of the attack.

Possessed of an admirable resilience, James has had to deal at various times

with a horrendous dancing injury, the strange spontaneous combustion of his

car, a bunch of weirdos living in his house, some burst pipes in his

bathroom, and being continually reminded of his misfortunes by sentences such

as this, but every time, he has come up smiling.

If there was a Club Reunion for the 1999 Jude

side, then would Jess Ball turn up? Would American Mike O’Leary make an

appearance, still batting like it was baseball and unable to straighten his

arm to bowl thanks to years of pitching? Would anyone recognise Phil Holt or

Gus da Cenha or Robert Phillips? Would that

sunglasses chick be there, even though she didn’t

play and was only ever around in 1998? Can someone stop me asking all these

questions? |

Begin | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07

|

“Part IV – 2000” By all accounts the Year 2000 was the turn of the

millennium, and a momentous time to be alive. There was suddenly a big ‘2’

where a tiny ‘1’ had used to be. Except for the ones who committed mass

suicide, millennium cultists everywhere were disappointed that the world hadn’t been destroyed in an inferno, though secretly

relieved that they were still alive and could now find something else whacky

to believe in. There were parties, there were fireworks, there was an

expectation of things to come. Then, after the Y2K Bug turned out to be a

global con organized by IT consultants, everyone became bitter and

disillusioned and began to hate life just as much as they had before. All the

hope in everyone’s hearts faded, just because of those IT guys, who would

never again earn a hundred quid per hour for sitting round doing nothing, but

what did that matter when most of them could now afford to retire? Anyhow,

Y2K was a big let-down and nobody gave a damn about

it in the final wash-up. The world wouldn’t be properly

changing until the 11th of September the following year. Chris Legg, manager of The Jude, played only one game for the team in 2000 before

marrying his girlfriend and moving up north to manage a sports store. Of

course, we were sad to see Chris go. Because it meant that his nurse fiancée

was going too. We all wanted that nurse, we wanted her bad, there was

something about her, something hot, something nursy.

We wished we knew what she looked like in uniform, we wondered if she ever

wore it off duty. We wanted to get injured or beaten up, go to A&E, see

if she was there. But Chris got her, and we could never figure that out. Was

he sick? Did he need looking after? Was that it? Martin Hurley was only

around for a single game too. He went off to work in Germany before moving

back to Ireland. Howard Jones, Mike Thorburn, Eddie Lester, James

Hoskins, Matt Bullock, Clare Norris, Antony Mann – the spine of the team

remained constant, but there were new players as well, some who would hang

around, others who made but fleeting appearances. Tony Mander and his son Ben

played almost 30 games between them in 2000, and young quick Greg Le Tocq from Jericho, who was not as quick as he thought he

was, played 12 in his only season for the team. Future captain Leo Phillips –

concert violinist, conductor, and son of the painter Tom Phillips – made his

debut, as did Adrian Fisher, whose own side, The Team With No Name, had lately become

The Name With No Team.

Local baker Ade Fisher (in blue, second from left) on a break

from his pie making. Jake Hotson’s first game for The Jude was against Stokenchurch

at the Cowley Marsh minefield-cum-rabbit warren, in the preliminary round of

the Bernard Tollett Cup. Ant Mann was skipper that

evening, and as usual had been scrabbling around

for days trying to get an XI together. In desperation he rang his friend

Simon Image, who had never played cricket before in his life. To punish Mann

for interrupting his drinking session, he put him onto Jake. A portent of

things to come, Jake turned up late, wearing black jeans and Doc Martins, and

spent the whole game staring at the sky trying to find Mandelbrot Sets in the

clouds. Fractal, man, fractal. “Hmm,” said Stokenchurch on the way to their

120-run victory, “We had no idea. We could have put out our second team. Or

the thirds. Or fourths.” Now, eight years on, Jake has cemented his place in

the team’s history, developing into a useful batsman, skippering on several

notable occasions, and taking on the role of the gavel-wielding Judge at team

fines sessions.

Not how it

started for Jake. Winning the quiz down at The Jude one night, local melancholic and poet Andrew Morley

joined the team as his prize, and went on to play 8 games that season, in a

melancholic and poetic way. 2000 saw Lorcan Kennan’s only 5 games for the

team, with 4 from Paul Drake, 3 from Nick Watney, and 6 from Paul Grant, who

was Ed’s neighbour in Bladon, and who copped my knee in his head one game

while we were both going for the same catch. At least I caught it, though. I

still remember the batsman – Mick Harrow from Nomads, who top-edged it to fine leg. Eight years after that

catch, just last weekend in fact, down at their ground in Duntiston

Abbots, I was having a chat with Mick while I umpired at square leg. Eight

years. There are people who die trying to take catches. They

run into a team mate at twenty miles per hour, who

is also running. That’s forty miles per hour of

impact. It can get nasty. On this occasion Paul didn’t

die, though he didn’t last long in the team. He met a girl who didn’t think cricket was much fun, for her, anyway. And

whilst it is true that all wives and girlfriends, without exception, don’t

think cricket is fun, and really do not understand why their better halves

have such a passion for such a ridiculous game, there are some who tolerate

the strange obsession, and some who don’t. Paul’s girlfriend didn’t, though maybe as well Paul wasn’t as obsessed as we

thought he ought to be.

Andrew Morley (centre) doing what he does best. Richard Hadfield played twice for The Jude in 2000, I don’t remember now

the connection which brought him into the side. He scored 72 against OUP at Jordan Hill on debut, a record

which stands to this day. He was the co-author of a novelty book which was

big that year, The Cheeky Guide to Oxford. Richard went

off to have children, but a tiny flame lingered in his heart, never

extinguished, ever burning, a desire gnawing away at him, and six years

later, in 2006, he came back to the side, walked out to bat, and scored a

duck. All in all, 30 players turned out for side that year,

many for only one game, but it didn’t make any difference who played – season

2000 was one of several Jude nadirs

which had begun with the team’s foundation in 1998. All teams have their

peaks and troughs, but The Jude

were no idiots. They had the foresight to get all their troughs out of the

way in one go. 2000 was particularly troughy. Of 17

games, The Jude won only 4, and

once again, these victories were mainly against weaker, scratch teams drawn

from irregulars. Once again the friendly natives of

Weymouth were awoken from their pastoral idyll, stirred from their haystack

slumbers or called in from pleasant afternoons pipe-smoking and a-fishing on

The Wey. The Jude beat them twice,

easily. There was another win, too, against The Old Tom, but that hardly counted either. There were many low points. All out 65 against The Baldons. All out 45 against The Marlborough (a recovery from

14-5). All out 50 in the game against Stokenchurch,

during which five wickets fell with the score on 19..

All out 34 against The Isis, after

being 11-6. And then – the usual insult – they brought their rubbish bowlers

on, the guys who only ever got a bowl when the game was so far won that it didn’t matter. But The Jude were so

crap, that’s all they deserved, the guys could only bowl full tosses and

half-trackers at six miles an hour. The guys who sometimes hit the pitch

between the wides. Every team has them, or if they don’t,

then they should. They’re an important part of

Sunday cricket. They make it what it is, a game for everyone, and everyone

for a game.

No caption

required. There were half decent performances against Lions Club and OUP – the latter of which was to become an annual fixture – but

the only ‘proper’ win of the season came against The Beehive. This was only the second Jude game played at Pembroke College Sports Ground, down

Whitehouse Lane, past the pikey van and loitering motorbike thieves, then

over the railway footbridge. By now The

Jude had a committee, with Matt Bullock as the no-nonsense Chairman,

Eddie Lester the earnest, idealistic, Captain and Secretary, and Ant Mann as

the honest but lackadaisical Treasurer, for whom the phrase ‘close enough is

good enough’ had been invented, especially as it related to accounts. The

previous year, playing Isis at

Queen’s College, we had envied the greenness of their ground and the

clubhouse and bar. We had wondered how to get one of our own, a better one,

with even more grass, taller trees, faster flowing perimeter streams, and

better-looking college girls playing on the adjoining tennis courts. As

chance would have it, Pembroke and their groundsman Kev were up for grabs.

Voila! Kev, Pembroke, The Jude, it was a three-way marriage made

in heaven, and completely legal. In retrospect, it was important to find a permanent

home. The Jude was not a village

team, so didn’t have a green to play on, and the

Oxford council grounds were already in the process of being neglected and

decommissioned. Cuttleslowe Upper and Lower soon

became just Cuttleslowe Upper, the Cowley Marsh was

always a dump, and the Horspath

nets were just a memory. On top of which, it was a rare treat when a

groundsman actually turned up to open the change

rooms. Hey, not that cricket’s very big in England, so it was no wonder

really that the local council should have zero interest in fostering the

game. The Beehive

fixture was a turning point of sorts. In these days The Jude were easy-beats, and it was

always an embarrassment to lose against them. Sure, they could take the odd

game here and there if Lee Davie turned up and played well, or if someone

incited Howard Jones to bowl like a man possessed, but this was the first time

they had won a true contest on their own merits, and a sign of the gradual

improvement to come. Set up nicely by a 73 from none other than Jones, The Jude defended 163-5 against a

strong Beehive side riddled with

Antipodeans and desperate to win, or rather, not to lose. But from 127-2, the

’Hive collapsed in the pouring rain

to all out 149 with 2 balls to spare, and for a change it was entirely due to

The Jude’s bowling and catching. In

fact, this was the year in which The

Jude’s began to have a bowling

attack, although the batting remained wretched for some time to come.

Pembroke, our

Theatre of Dreams. Antony Mann was Player of the Year in 2000. Thought he

bowled stiffly like some kind of automaton, like he was on a cliff edge and

afraid to look down, his left-arm in-swingers had suddenly started to work,

and he took 21 wickets at 12.90, with a best of 4-7 against The Old Tom. He also scored 155 runs

at 14.10 with a top of 39. Greg Le Tocq bagged 18

wickets at 13.39, and Ed Lester 17 with his looping spin. Howard Jones played

only 7 games, but topped the batting averages with

221 runs at 44.30. He hit the team’s highest individual score (that 73

against The Beehive at Pembroke) and also took 10 wickets, including a best of 5-9. At his

best, he was good, moving the ball both ways at speed and hard to play. James Hoskins had settled in nicely with his slow

right-armers, taking 10 wickets in 7 matches at 19.00. Mike Thorburn once

again went through the year in an alcoholic haze, slurring and stumbling his

way to 115 runs at 16.43 and 9 wickets at 22.77. Though handicapped somewhat

by his love of the amber nectar, Mike was a sound length bowler who just

about always broke partnerships – he very rarely went a game without bagging

a scalp. In 2000 Andrew Morley took a wicket and had an economy rate of 4.57

runs per over. Ben Mander took 4 wickets, but also bashed 64 runs at 4.92.

Matt Bullock scored 65 runs at 4.65, but made a

remarkable 14 catches and 8 stumpings behind the wicket. Clare Norris scored

18 runs in her 10 games, she was still finding it hard to get the ball off

the square, while Jake Hotson scored 24 in 9 at an average of 3.43, ditto:

ball, hard to get off square. Leo Phillips actually looked like a batsman,

which confused everybody for a while, especially his own team

mates. He played in 8 games, making 177 runs at 19.50. In his first

year, Tony Mander was 4th in the batting averages, very hard to

dismiss, scoring at 19.33. Come to think of it, I remember it well, this year. I

remember Noel Reilly playing against The

Beehive at Swindon, being stretchered off after scoring 3 because 66

yards was all he could manage on his two spindly legs. I remember the

European Cup on the telly in the pubs, England bowing out on penalties as

usual. The way The Rose & Crown

brought a Cambridge Blue to play for them, and how it felt watching a proper

cricketer, how it felt bowling to him, trying not to get tonked

all over the ground. How pissed off we were because they’d

brought the guy in the first place. Trying to keep out Haider, the

Stokenchurch first team quick, on Cowley Marsh. Watching everyone else trying

to keep him out, one after the other, as those five wickets fell with the

score on 19. The new millennium, the idea hanging in the air, a new start for

everyone, another thousand years just begun, and anything was possible. The Jude’s first year at Pembroke. |

Begin | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07

|

“Part V –

2001” Anything was possible, but certain things weren’t very likely. The

Jude winning a game of cricket being one of them. Having said that for the

sake of taking a cheap shot, it’s fair to say that

2001 was much better for the team than the previous year. There was only one

pathetic collapse to rival the usual debacles, when The Jude showed up to play with just 9 against The Nomads at Liddington. They batted

like rubbish to be all out 42. There were only 13 games in 2001. There was no

tour. The Jude lost 9 and won 4,

but except for the game against The

Marsh Harrier, where Adie Fisher captained a bunch of drunkards in Doc

Martins to a heavy defeat, the wins were good ones, and many of the losses

could have gone either way. Featuring in that Nomads

game, the first of the season, were two players who had never

before worn the Jude colours

(white with a white trim, white shoes, generally white). Steve Dobner was an

Essex boy, a friend of James Hoskins who had never really played much

cricket, but who was possessed of that strange kind of natural athleticism

which made it look like he had. Pretty soon he was among the runs and

wickets. In many ways, he was an archetypal bowler. A genial and friendly guy

in the normal course, as soon as he grabbed the ball, something began to

bubble under, be it frustration at not hitting the length, or a desire to

kill the batsman at the other end. Thornton Smith was a different kettle of

monkeys – well-read, laid back, with a sharp mind and an eye for the non sequitur. As a cricketer, he was

more of a golfer, but supremely effective in his crosswise batting style,

which always brought quick runs if he could stay at the crease.

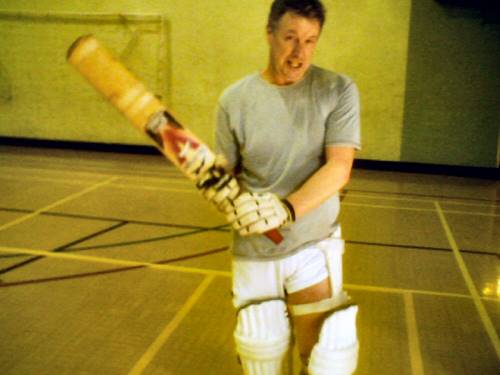

Thornton Smith holding a trusty squirrel basher. 2001 saw the departure of Clare Norris, who married

boyfriend Julian and prioritized herself into moving to Australia with a

growing family. Mike Thorburn played only one game for The Jude in 2001 before shaving his head for charity and moving

up to Manchester with his girlfriend. Publicans all over Oxford mourned his

leaving as beer profits across the county plummeted, while the local

Sarcastic Comment Quota dipped noticeably as well. As for Greg Le Tocq, he left Oxford quickly to study at Nottingham, though

not as quickly as he thought he did. Otherwise, things had a settled feel to them, with

Howard Jones, Adie Fisher, Ant Mann, Matt Bullock, the Manders

(including cousin James), Jamo

Hoskins and Jake Hotson still making up the core of the side. Paul Drake was

another of the Mander clan, by marriage, who played sporadically. Ed Lester

was still around, but relinquished the captaincy in

favour of Leo Phillips. Leo was a good skipper and a decent bat, but problems

with gout among other things meant that he was around for only 7 out of the

13 games, and it was to be his last year for The Jude before he sold up and moved to the Far East, settling

eventually in Thailand. After the pathetic loss to the Nomads, The Jude

regrouped in time to lose against Marlborough

House at Corpus Christi. This was the Golden Age of the long-running

rivalry with the Marlborough boys

which went on for at least three or four years. In this Age of Goldenness,

the teams were evenly matched, and there was niggle, even sledging, and sometimes

camaraderie and mutual respect. The return match at the Warneford Hospital

ground was Lee Davie’s game, and his half century from a mere 21 deliveries

is a Jude record unlikely to be

beaten any time soon. With Howard Jones contributing a characteristically

aerial 63, The Jude easily defended

213-4, still their fifth highest score of all time. The first game of 2001 played at Pembroke was against a

new opponent, the Bodleian Library,

and The Jude chalked up another

win, by 12 runs, with Adie Fisher scoring 41 and taking 4-18 with his

deceptive two-paced multi-trajectory pie. The next game saw yet more

newcomers at Pembroke, but things didn’t turn out

quite so well. Queen’s College old boys Lemmings

were entertained by a pitiful 6 Judesters, with an embarrassed Mann skippering the motley

crew. It might even have been 7, but James Mander decided to get a haircut

instead of fronting up as promised. Thanks for letting us know, James. Hope

the cut worked out well for you. Neater and tidier, was it? But the Lemmings weren’t

dicks about it at all, and even lent The

Jude John Greany. His 70 wasn’t enough to stave

off defeat, but the Lemmings were

too nice to feel sorry for us, which can’t be said about all those other

bastard teams who kicked us when we were down.

Maybe Ben

Mander should have gone for that haircut instead. The 13-run loss against the South Oxford Social Club at Horspath was notable for two things:

Lee Davie reaching 97 not out after being dropped five times – all of them

straight forward chances – and Steve Dobner, playing for South Oxford, diving

full-length into the dust on the last ball of the game to cut off the

boundary which would have given Lee The

Jude’s first ever century. Well done to Steve, who filled in for South

Oxford at the last minute and was rewarded with batting last and not facing a

ball, not getting a bowl, and fielding in the deep all day. Showing the kind

of dedication which would endear him to everyone except girlfriend Kim, Steve

had driven all the way from Stevenage to Oxford only to end up as twelfth

man, so had leapt at the chance to play some cricket. But subbing for the

opposition is always a lottery. On the one hand, the skipper is glad that he

has an extra player to make up the numbers, but on the other, he doesn’t have a clue who you are and if you can play. And

when he asks you if you bat or bowl, you’re most

likely to say something like, Yeah, a

bit of both, but I’m not very good. At which point you disappear from his

game plan completely and end up at fine leg for the duration. The season’s decider against The Marlborough was at Pembroke. It started with niggle, followed

by mutual respect, after which came bewilderment as people began to realize

that Jake Hotson had turned up to the game with somebody else’s arm, and was

using it to bowl. 5-28 was the return, with 4 clean bowled, as a useful Marlborough batting line-up fell for a

lowly 120. During this game, the redoubtable Dan Edwards fell lbw to Ant Mann

for 5, though no doubt this decision was a complete injustice as Edwards had

put in a big stride and the ball was most likely either hitting outside the

line or sliding down leg. In those days, Edwards was a true journeyman, often

trawling round the grounds of a Sunday with his kit bag over his shoulder,

his cries of ‘Anyone need a player?’ echoing across the fields. With his

broad-rimmed head sitting under his broad-rimmed

hat, Edwards was a diligent foe hard to dislodge, a lover of banter, the

forward defensive and the back cut. But this was Hotson’s hour, and during the innings

break, he held the ball aloft in the style of Glenn McGrath, and there was

much premature gloating as a team photo was taken. Some say it made The Marlborough angry, others that The Jude batted like crap. Whatever

the case, a hard-fought 88-3 soon turned to a parlous 98-8, and Ed Lester was

last man out, run out for 24 with the score on 106, 14 runs short of victory.

Jake when he could bowl, holding the ball aloft. Eddie Lester

with Ruth on the left. Adie Fisher padded up. Tony and Ben Mander front row right. The last game of the year was The Jude’s finest, a 36-run win against the strong Nomads at picturesque Cuttleslowe, the best of the council grounds. The damage

was done by Ant Mann’s career high 58, and Howard Jones, who made a

characteristically aerial 57. It was a note of triumph on which to end the

season, though there was scant triumphalism. The Jude were still Sundayists at

heart, mostly pissed on the sidelines and reading

the newspaper. Occasionally a player would look up from his warm beer and

sleazy tabloid to realize that a wicket had fallen

and it was time to saunter out to flay the bowling for a handy 6 or 9, but

mostly, not. Despite playing in only five games – or perhaps because

of it – Lee Davie was Player of the Year in 2001. He averaged 77 with the bat, and took 8 wickets at 12.50. Howard Jones had another

good season, recording The Jude’s

highest run aggregate of 298 at 37.25, and taking 10 wickets. Adrian Fisher

made an impact in his first full year with the team, with 161 runs at 23.14,

and a selection of fine pastries and sausage rolls for a return of 9 wickets

at a niggardly 11.67. As for Jake Hotson, the proof that he could once

actually bowl before the yips began to eat away at his scattered psyche lies

in his bowling figures. He sent down 19 overs for 7 wickets, at an average of

10.85, with an economy rate of 4.00. That was second only to Ant Mann, who

took 17 wickets at 9.88, conceding just 2.60 runs per over.

Ant Mann – the

personification of smug. Leo Phillips’ top score as skipper was 44 not out,

while keeper Matt Bullock scored 99 runs with a high of 28. Tony Mander’s highest score was 34. James Hoskins took 4

wickets and scored 40 runs at 8.00. Thornton Smith’s first 6 games for The Jude saw him score 16 runs at 5.33

and take 3 wickets with his skiddy medium pacers. It couldn’t be said that The Jude were resurgent in 2001,

because they had never been surgent in the first place. But they were hanging

in there as an entity, more or less, and that flimsy fabric which had been

blowing about a few years back was still fluttering gamely in the breeze,

though there was perhaps the need for a few more heavy rocks to weigh it down

and stop a strong gust picking up the whole fucker and blowing it to pieces. |

Begin | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07

|

“Part VI –

2002” With Leo Phillips fleeing the country at the start of

the season, an unhappy Matt Bullock took over the captaincy of the side. Not

that Matt was a poor choice, he was just the least reluctant of the various

candidates who hid under the table when the question was raised. Too slow in sliding

out of his chair and disappearing from sight, Matt

was left to clasp disconsolately what for another year at least would be the

poisoned chalice. Among other things, the new captain oversaw a new name

for the team, as Jude the Obscure

became Far From The Madding Crowd CC.

Landlord of The Jude Noel Reilly,

the team’s patron, mentor and guru when he wasn’t busy falling down pissed as

a newt, had lost his job, and the team had moved their base to Noel’s new

concern in Friar’s Entry, another pub by Thomas Hardy. Smack bang in the

middle of town, it was actually pretty close to the

madding crowd, but the madding crowd didn’t seem to know much about it,

because it was most times empty. In 2002, apart from losing Leo Phillips to the Far

East, Adie Fisher was absent due to family reasons. Howard Jones all but

retired, while Lee Davie played 2 games and vanished, though not literally.

He was still around, just not within sight. Leo was strictly a batsman, but

the other three were all of them useful all-rounders, and the void was hard

to fill, even more so as no new players appeared to fill it. This explains

why, out of a potential 121 places (11 games) during the season, only 108

were taken. The Mad were often

short, and often beaten. Many of the regulars remained. Ben and Tony Mander, Ed

Lester, James Hoskins, Matt Bullock, Antony Mann and

Jake Hotson were there for just about every game, as were Thornton Smith and

Steve Dobner.

Steve Dobner (right) gets a massage off his ‘gal shortly before

his next 12 rounder. In 2002 The Mad

lost 9 of those 11 games, and it’s no accident that one of their two

victories, a convincing win against The

Marlborough at Boar’s Hill early in the season, was by a side which

featured the soon-to-be-missed Jones, Davie and Fisher. They scored 99 runs

between them, and took 5 wickets – and yet, were somewhat overshadowed in the

eyes of some by the heroics of James Hoskins, who belted his highest ever

score of 35 in a partnership of 111 with Davie, for a long time a Mad record for all wickets, and still

a record for the 4th. Losses to The

Bodleian and Nomads were

followed by a humiliating thrashing against Lemmings, a game during which Dylan Jones made his debut. Jamo’s lodger, Dylan was a Welsh rabbit with the bat, but

could bowl handily at times and often took wickets. Jones must have been less

than thrilled to be playing his first game for The Mad as the Queens’ College boys racked up a savage 276 from

just 35 overs and won the game by 196. Another mauling, again from The Bodleian, preceded a brutal

pasting by the OUP. Thank God,

then, for The Marsh Harrier, who

were even worse than The Mad even

when The Mad were worse than

everyone else. They turned up at Pembroke to match The Mad’s own depleted side in numbers

at least, but The Mad were

victorious as The Marsh dried up in

the sun. A win is a win, I guess, but sometimes it’s more like just standing

in the heat of the afternoon waiting to go to the pub. Adie Fisher was The Marsh captain that day, and he

suffered from Saturday night’s promises, broken on the Sunday as all the

pissed guys who had said they would play decided they couldn’t be bothered

and left him hanging out to dry. Adie: You’ll definitely be

there tomorrow, won’t you? Because

if you won’t, then tell me now, because I need to

know for sure, otherwise we won’t have a full team. Pissed Guy Lying On

Floor In Pool Of Own Urine: Oh yeah,

man, yeah, I won’t let you down.

The following game, a typical grudge match again The Marlborough at Pembroke, summed up

The Mad’s

deplorable season. Bowling first and skittling The Marlborough for 77 (Dylan Jones 4-17) made The Mad feel good for roughly half an

hour. There followed a lengthy period of feeling bad, as The Mad tumbled to all out 51. A violent 33 from Thornton Smith

was not enough to get The Mad home.

No surprise really, when the side’s second highest

score was Ben Mander’s 4. There were four 0s, and

four 1s, and a useful 3 from Steve Dobner. The 2002 tour was largely a washout, as the team drove

into drizzly Cornwall and registered a loss against a Callington side which didn’t really want

to be there. The Mad went ten-pin

bowling, went to the Eden Project, then went home. Best of the batsmen who played regularly in 2002 were

Thornton Smith and Ben Mander, but their averages of 14.00 and 13.50 respectively

tells the story in itself. Nobody except Lee Davie

scored over 50 during the entire season, with Matt Bullock’s 39 the next

highest mark. Ben Mander had the top aggregate – 108. In a bad year for just about everything, Ant Mann was

Player of Season again for his 9 outfield catches and 14 wickets at 10.57.

Ben Mander took 9 wickets at 21.33, Steve Dobner 8 at 23.63. James Hoskins

bagged 7, with Ed Lester and Jake Hotson both taking 5. Thornton Smith took 4

at 14.50, and five catches.

Poring over a

poor 2002 – a deflated MAD. 2002 had seen a new name for The Mad, and a new skipper, but whatever hopes of success had

been cherished at the start of the year had quickly evaporated into a losing

mentality as the team realized they were no longer good enough to compete

against even the mediocre teams they were facing. They had brought the idea

of a nadir to a new low, and there wasn’t much room

left for going down. They had scraped the bottom of the barrel, taken the

bottom off, climbed down under the barrel, and were now digging into the

ground. Traditional foes were getting sick of The Mad and the easy victory they always provided. Even The Marlborough, themselves in decline

as their home pub began to ooze and flake with that decrepit, post-nuclear

holocaust style of décor so enjoyed by hard drinkers and blind people – even The Marlborough were secretly treating

The Mad with disdain and scoffing

at their plight in an excess of gloating and schadenfreude which The Mad

themselves could only dream about being in a position to do. If the team couldn’t find new players, and fast, then there was a very

real danger it would fold, in an utterly tragic and dramatic way. |

Begin | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07

|

“Part VII –

2003” They say that it’s always

darkest before the dawn, and while that is obviously a load of rubbish – it’s

usually darkest at about three in the morning – in this case, they were

right. New players were needed, and new players were found. 2003 marks the

first year of a modern Mad, with

aspirations beyond scoring a single then getting out, and the new blood that

flowed into the side back then remains to this day. The Mad didn’t

lose any regular players in 2003, but they did gain six. Thornton Smith,

Antony Mann, Ben and Tony Mander, Steve Dobner, Jake Hotson, James Hoskins,

Matt Bullock, Dylan Jones and Ed Lester were all

still playing. Joining the ranks were Ian Howarth, Martin Westmoreland,

brothers Nick and Steve Hebbes, John Harris, and Graham Bridges. Nobody yet

knew it, but a gradual process of change had begun. The smiling ‘aw shucks’

losers of the last few years, apologetic and polite, would in time give way

to a harder, more competitive Mad,

which on occasion would push against the confines of Sundayism

and wish for more.

John Harris holds the record for best bowling figures, though it

was against The Marlborough. A clash of cultures was inevitable, as the die-hard Sundayists, entrenched in what they saw as ‘their team’,

muttered to no-one in particular about ‘a fair go for everyone’, while some

of the newer players began to speak of ‘putting out the best side, especially

in important games.’ This is a common dilemma which underlines just how

difficult decision-making in Sunday cricket can be – far tougher than league

or grade, or even first class or Test cricket. In Test cricket, while there

may be arguments as to who the best players are, the aim is always to select

the best, whereas in Sunday cricket, there are other, more subtle

considerations. Such as, when and how often should

the crap players get a game? Should the crap players be selected when it is

their turn, or should they only be allowed to play against crap opposition?

Should players new to the team get the same number of games as more

established players, or should they be regarded with utter disdain and left

waiting months or sometimes years before they are allowed into the starting

XI? Does a solid team player who serves on the committee/writes reports/comes

to nets/does the umpiring and scoring/generally gets stuck in get rewarded

with more fixtures than the slacker who couldn’t give a toss and just pitches

up half pissed expecting to open the batting and bowling while keeping wicket

at the same time? Being on the committee myself, I think the answer is pretty clear. Certainly it’s true

to say that if everyone worked as hard for the side as everyone else, then

there’d be no opportunity for the control freaks to be in charge. Things were further complicated for The Mad, though, because the idea of a

best team was an alien concept – previously, there never had been a best team to put out. Often, there never had been a team. In truth it took a while for

everyone to get to know one another, and to realize that they were all just

as neurotic and insecure about their place in the scheme of things as

everyone else. Some people just showed it more. Whatever faint nostalgia there may remain for the days

of that quirky bohemian loserdom which so often

characterized The Jude, there is

little doubt that the side would not have survived more than another season

of it. 2003 saw the start of better days, though sometimes they still seemed

a long way off.

Chairman Matt

Bullock (right) grew weary of soulless beatings and resigned as skipper after

2002. In contrast to the usual method of electing the

committee – through consensual non-election of whoever was willing to take

the job – the 2002 AGM saw a real and actual contest for the position of team

captain. Chairman Matt Bullock hung up his coin in utter relief and vowed

never to captain any sporting side anywhere ever in the world again, and in a

controversial move, James Hoskins went head to head with Ed Lester for the

post. In a vote for the future, Barrack Obama style, Hoskins won the ballot

and became The Mad’s

fourth official skipper. Lester, Phillips and

Bullock had all served before him. How would Hoskins’s tenure work out? Things started well for the new skipper, with a good

win against a decent Bodleian side

at Jesus College. It was an unusual looking Mad scorecard that day – Martin Westmoreland 38, Nick Hebbes 28,

John Harris 21. Steve Hebbes took 2-8, while Steve Dobner, growing into his

role as an all-rounder who would often vow to never bowl for The Mad again, picked up 3-8 and

scored 17 not out as The Bodleian

crumbled to all out 55. Westmoreland, a friendly northerner who had left the

rugby league, mills and coal mines of his youth for a better life down south,

was like many batsmen at this level in that he had just the one scoring shot

– in his case, a lofted smash towards cow. The off-side has always been for

wimps and arty types, and Martin – soon to be dubbed ‘Moo’ – knew that better

than most. His bowling, though sometimes wayward, swung late, sliding away

from the right-hander, and bagged him a fair share of the wickets. Nick

Hebbes was also a right-hander, a solid opener whose only real weakness was

playing across the line to the straight one. Nick, though, was often called

on to steady a sinking ship. He also bowled effectively into the corridor

with a loping run-up, his left elbow appearing to flap in the breeze. His

brother Steve, shorter yet with generally the same shaped head, was a

deceptively clever right-arm spin bowler and at time useful batsman in a

pinch. Hebbes Jnr brought a kind of quirky good-naturedness to the side, and

it was shame that he played only the two seasons. John Harris batted with an

understated elegance which looked often as though it might have brought him

more runs. He bowled slow and often confusing spin and took great catches in

the outfield. The Mad lost to The Marlborough at Cowley Marshes, all out 82 on the mole colony

which passed for the cricket pitch there. Watching Dan Edwards bowl for The Marlborough that day reminded me

of the kaleidoscope I got for Christmas when I was eight. The hypnotic

spinning, the distracting patterns, it was all there in Edwards’ gyrating

arms. Whereas many bowlers attempt to hide the ball as they run in simply by

concealing it, Edwards was more overt in his deception, opting instead to

hide it in the flurry of his whirlpool action, producing it always at the

unexpected moment, like a conjuror taking a coin from behind your ear. Genius

or madman, it was his 4-19 that made the difference, cunningly exploiting the

rutted wicket clearly prepared by the groundsman with some kind of giant

gouging tool, then stampeded by a herd of wildebeest before being scarified

with a harvester. The depth of Oxford Council’s indifference to cricket in

general could be seen by their attitude to the footballers who used the

Cowley Marsh pitch as a playing field during the summer months. Frankly, they

didn’t give a toss, and as soon as they could be

bothered to realize that there was a problem, they solved it in the way

councils usually do, by ignoring it and letting things slide. Eventually the

unplayable pitch was finally decommissioned and given over to studs.

Cowley Marshes as we’ll always remember

them. The game against South

Oxford Social Club, also at Cowley,

saw yet another Mad debut.

Cornishman Ian Howarth, originally from Oldham, had turned up at the ground

by mistake thinking it was a pub. An old friend of Thornton Smith, Ian was a

destructive and provocative batsman who, despite saving his culture for the

canvas – he was a painter and musician in his spare time – over the years

scored hundreds of runs for The Mad.

My favourite memory of Ian will always be the look on his face after I bowled

him with a slower ball while playing for The

Bodleian, as he tried to launch me out of the ground. Yet against South Oxford that day, The Mad went down by 47, in the

process finding a batsman who could score runs while still pissed from the

previous night. Howarth soon became an important cog in the Mad machine, and

was instrumental in setting up the first Mad

website, which has established an international presence for the team and

is probably the best of its kind in the world. In Wootton &

Bladon, The Mad found a

ready-made rivalry, with the sometimes abrasive but ever competitive Steve

Poole turning out to be The Mad’s nemesis at Horspath, where his disdainful and

insouciant 57 took the game out of reach. But the return match at Wootton was a different species of

aardvark. Batting first on the slow and undulating village pitch, Ian Howarth

swung at anything in the arc, and in Thornton Smith found a willing

accomplice in the carnage. Howarth (89) and Smith (58) put on 133 undefeated

for the fifth wicket on the way to 202-4. The provocation and gamesmanship was mutual, with Howarth and Poole doing their best to rub

each other up the wrong way, though it was Howarth that day rubbing noses in

it. It got so bad Tony Mander umpiring stepped in and threatened to dock the Wootton boys 5 runs for the verbals. The Mad

won by 45. It was the start of something special, especially with Pooley.

Ian Howarth

with a drink to match his ego in Somerset in 2003. In July The Mad lost by 52 runs to The

Bodleian at Pembroke, with Nick Millea scoring

78 out of the Bod’s 165. It was a

good day too for the Bod’s Andy

Mackinnon, who destroyed the Mad

middle order, taking 4-11 in 3 overs of apparently awkward pie. Eddie Lester

was one of the victims, given out lbw for nought by Ant Mann, playing across

the line to a straight sausage role that would have hit just above the

shoelaces. Sometimes it’s difficult to tell with

Sunday umpiring – is it fair or isn’t it? The fact that you have to umpire

while your own team bats can make for colourful debates in the pub later,

especially in relation to the lbw law, which is properly known on average by

22 percent of any given Sunday side. Lbw decisions are given roughly in order

of seniority, so that a respected batsman who will have a tantrum if given

has a one in three chance of actually being

given to a plum shout, while a lesser player who will just shrug and wander

off the field has a three in four chance, four in five if the ball is

pitching outside leg, which is of course not out under the law, but how on

earth is everybody supposed to remember complicated details like that? There

are exceptions to this rule, namely, if the respected batsman is also a dick

and generally despised, i.e. not respected at all, then his chance of dismissal

rises to almost one hundred percent per appeal, no matter where the ball

pitched. Eddie had been having trouble with his batting, playing

across the line to straight balls which either bowled him or trapped him in

front. He was fine in the nets, keeping a straight bat and playing through

the line, flaying the bowling to all parts, but as soon as he walked to the

crease, something clicked inside him and he played a duff shot which brought

his downfall. He hadn’t scored a run in weeks. He was

desperate. This was his big chance. So Mann gave him

out first ball. It was a fair decision, but nonetheless, not fair. In 2003 The Mad

toured West Somerset and staying at The Dunkery Beacon, a huge bed and

breakfast place perfectly suited to large groups of the semi-coherent. I

didn’t go on that tour, so I don’t know much about it, though I did hear the

fascinating stories that people brought back with them, the outrageous tales

of falling down in the gutter and of wearing lampshades on each other’s heads.

I can’t remember now who won the tennis tournament,

or who ate the most pickled fennels with their hands tied behind their back

at three in the morning, and for that I am eternally grateful. There was also

some cricket on the tour, three games, and three losses – to Minehead, Timberscombe and Stogumber.

Incidentally, Stogumber is rhymed

with ‘number’.

The Dunkery

Beacon hotel – home to the FFTMCC for three consecutive tours to Somerset. The Mad played four games against The Marlborough that year, winning two

and losing two to keep the old-standing rivalry on an even keel. There was

not much sign of Mike Reeves, but Dan Edwards was ever present, The Marlborough’s key performer thanks

to his obdurate batting, his spellbinding bowling style, and his

indefatigable wide-brimmed head. The last game of the season was against them, and turned out to be Ian Howarth’s greatest

near-triumph. His 97 out of 200-8 equalled the team’s highest individual

score record set by Lee Davie several years previously, and it’s just a shame that he holed out with only three runs

to go. There was still no Mad

player who had registered a century, though Howarth now looked the most

likely if he could just control himself and not act like such a twit. In his first season as skipper, out of 20 matches,

James Hoskins steered The Mad to 7

wins, a massive improvement on 2002. A glance down the averages for 2003

reveals that six of the first seven batting places were taken by players new

to The Mad. Premier batsman, and

Player of the Year was Ian Howarth, who averaged 40.69 with the bat while

accumulating 529 runs. In his bowling style he seemed often like the

reincarnation of Chris Legg, interspersing as he did his out-of-control

beamers with occasionally volatile medium pace. He took 8 wickets with a best

of 4-17. Thornton Smith stepped up a gear to hit 349 runs at 21.33 with his

flat-bat baseball style, relying as he did on a good eye and picking the

length. Newcomers Martin Westmoreland, Nick Hebbes, John Harris

and Steve Hebbes filled the next four places, averaging between 12 and 19.

Westmoreland’s highest score was 66. Pick of the bowlers was Ant Mann, who took 27 wickets

at 10.52, an aggregate wicket tally yet to be bettered. Stephen Hebbes bagged

an impressive 19 at 17.37 with his fast and skiddy spin, while Steve Dobner

and James Hoskins took 15 and 13 respectively at around 22. It was useful

attack now – Dylan Jones (12) and Ben Mander (11) were also among the

wickets, while Howarth, Hebbes the Elder and Martin Westmoreland could also

be relied on to pick up key scalps. John Harris took 4 wickets at 17.00 in

his three games. Westmoreland was also a revelation in the field, taking 12

often spectacular catches and affecting a run out.

Steve Hebbes

pictured at Pembroke. Graeme Bridges didn’t have a

great year with the bat, but he was always an asset to the side, and it’s a

shame he didn’t play for The Mad much longer. He had the thin build

of a distance runner, so it’s handy that he ran

distance races. Maybe he just preferred running to cricket. And one thing you

don’t get a lot of in cricket, Sunday cricket

especially, is running. In many ways this was

a new Mad, playing harder, winning

more, with players who wanted more to win more and harder, and not afraid to

take on the opposition where it sometimes counted more than on the field – in

the mind, or in the case of Steve Dobner, the car park. But glimpses of the

old Jude could still be seen in the

team’s general good humour and willingness not to be a bunch of dicks. Sundayism wasn’t dead, it would

just have to find a new way to exist as the times changed around it. |

Begin | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07

|

“Part VIII –

2004” As it always did, the team overwintered, with most

people going their separate ways, returning to hang out with their families

or whatever else it was that players did in the off season. The fact is, for

some of the side, cricket was just about all they had in common, and the team

spirit which carried them through the summer months didn’t have the impetus

to make it through the winter as well. There was one social occasion,

however, which brought a few people out of the woodwork. Ant Mann’s book of

short fiction, Milo & I, was

published in late 2003 and launched at Far

From the Madding Crowd. A remarkable volume containing the Dagger-winning Taking Care of Frank and the

innovative Shopping, it appeared to

universal acclaim and went on to sell thirty-six copies. The book launch was

a convivial affair which, as with all good literary events, ended in

violence. Re-enacting some classic scenes from Marx Brothers movies, Ian

Howarth (Harpo) pushed Steve Dobner (Chico) off his chair, Dobner retaliating

was thrown out of the pub, and Thornton Smith (Groucho) broke his wrist

trying to smack Howarth in the face. James Hoskins playing Zeppo saw the whole thing and remained unscathed, while

the rest of the idiots, when the booze wore off the next day, all had a date

with an A&E nurse. But despite the undoubted success of the book launch,

there were questions being raised about where the team should drink. Far From The

Madding Crowd was inconveniently right in the middle of town, and it

lacked atmosphere. In addition, The Mad’s spiritual guide and totemic figure Noel Reilly

was no longer the landlord. With this in mind, a crack team of researchers spent

much of the off-season visiting as many pubs in Oxford as they could, rating

them on convenience to Pembroke, beer, atmosphere, landlord friendliness, and

the chance of being beaten senseless by skinheads. Then, a committee meeting

was held in a neutral venue, the Harcourt Arms in Jericho. Deliberations went

on long into the night. The Folly Bridge Inn on the Abingdon Road was the

clear winner. It was close to the ground, it had a beer garden, the landlord

was all right and would give the team a huge wodge of cash to come drink

there. But something wasn’t right. Was it the

skinheads? There were some there, and they looked kind of mean and nasty.

What if they wanted to join the team, were refused, then killed everyone with

broken off pool cues? For the sake of saving everyone’s lives, it was decided

that the team would drink at the Madding

Crowd for one more year.

Martin sporting an early nickname. 2003 had been good, but in 2004, it got better. The Mad won 9 and lost 11. From time

to time there were still the abject collapses, but by and large they were a

thing of the past. As far as the team went, no new regulars were required to

swell the ranks. Dylan Jones was already cutting back his involvement,

and played in only 5 games. There was no sign of Ben Mander, but his

father Tony was there for 10. Andrew Morley returned from the abyss to play

in 7, and Adrian Fisher was back for the full season. Ed Lester played in only 5 games, but it turned out

that his mind was on other things. The Founding Father of The Jude was already planning to

emigrate to New Zealand with his wife Ruth, and his involvement in the side

lessened as the year went on. Ed was the driving force behind The Jude’s early development, building

the team from scratch. Without him, there would have been no Jude or Mad at all. Apart from this legacy, Ed had also coined the phrase

not at this level, to describe his

thoughts on the application of the lbw law in the arena of Sunday cricket.

The thinking behind the not at this

level philosophy is straightforward: Sunday cricket umpiring is so

uniformly bad, with most players not even knowing the laws, that no lbw

decisions should be given at all, as they are bound to be based on

misconceptions, bias, or cheating. To be fair, the not at this level school has many adherents, but the idea does fall down in the practical application, as demonstrated by

the Dave Shorten Example. Mad

bowler Dave Shorten used to play in a Sunday type team which banned lbws, for

precisely the reasons set out in the not

at this level philosophy, but

all that happened was batsmen stood directly in front of the stumps, making

it impossible to bowl them as well. Thus, while admirable in its intent, the not at this level concept is just not

practical, at any level. Even so, it is common even today to hear the phrase

ring out, accompanied by the throwing of bats and sundry cricket gear as a

player stalks off, definitely not out, but given anyway by some klutz with a

trigger finger who doesn’t know the rules. Or maybe, who does. Fluctuating fortunes were on show in the first game of

the season, as The Mad met old foes The Marlborough at the breezy Cuttleslowe

Park. The Marlborough had been decimated by departures. Mike Cox had gone,

there was no sign of Edwards or Reeves. It was a motley crew of jeans wearers

and the like who showed up to be skittled for 47 chasing The Mad’s 196. The Marlborough were headed where The Mad had almost gone, towards oblivion and dissolution. Jake

Hotson and Ian Howarth opened the batting for The Mad, putting on 65 for the first wicket. Of which Hotson

scored 4. Steve Hebbes remained 30 not out. Of The Marlborough’s ten wickets, seven were ducks. Only the loquacious

Mark Shelley held out, defiant, unbeaten on 20 at the end.

The

loquacious Mr. Shelley pictured at Cutteslowe. There was another sign of the times the following week

as The Mad recorded their first

ever win against OUP, a team which

had always beaten them easily in the past. The omens had been good – Ian

Howarth and skipper James Hoskins had spent the night pissed in Howarth’s

back yard, waking at dawn after half an hour’s sleep covered in dew and with

the cat’s tongue up their ear. So it was no wonder

that Howarth slapped a quick-fire 52 to put The Mad on course. This

time the opening partnership was 73. Jake Hotson scored 6. For a time, OUP were on course to reel in the

runs, but seemed to lose heart as the wickets fell, and all

of a sudden, it occurred to The

Mad that they could win this game. It all ended with a whimper, and a 44 run victory. Nick Hebbes took 4-17. The Mad played a new opponent, University Offices, at Cuttleslowe Park. This was the team’s first look at

Andrew Darley, who took 3-26 with his probing right-arm cutters and backed up

with 19 runs. But when Ant Mann took wickets with his 6th, 8th,

10th and 12th deliveries, The Offices were reeling at 4-3. It looked all over. It wasn’t. Abbas could bat as well as bowl. Despite gutsy

late breakthroughs from Hoskins, The

Offices edged a close game by two wickets, with Abbas remaining on 108

not out in spite of Steve Dobner’s

efforts from behind the stumps to sledge him into making an error. The return saw The

Mad win a nail-biter at Cowley Marshes. A rain break saw The Offices recover from 85-8 to all

out 135, as Latif and Chris Heron took the bowling on. Only a brilliant